Truth About the 1918 Spanish Flu Pandemic

From an exclusive interview with Lawrence Broxmeyer MD

LewRockwell.com

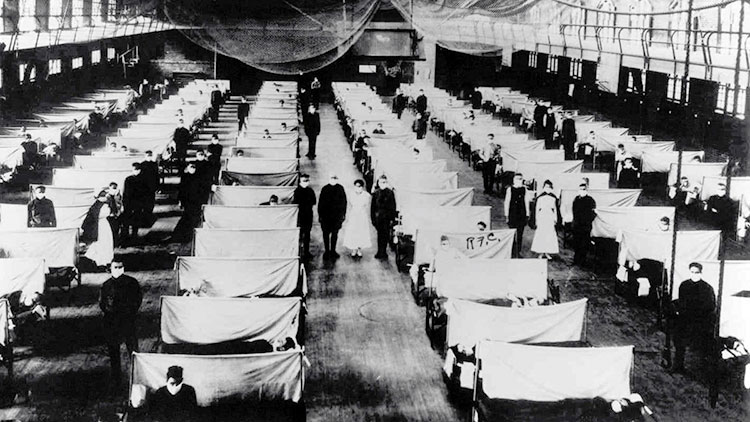

The 1918 Spanish Flu Pandemic

Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it

While “experts” have been telling us to wash our hands, have they really been doing the factual research needed to compare COVID-19 to say the Great Pandemic of 1918? Dr. Lawrence Broxmeyer MD, whose writings were previously published in the highly ranked The Journal of Infectious Diseases, doesn’t seem to think so. And his views, as expressed in an upcoming publication, aren’t alone.

During the SARS coronavirus outbreak, Wong et al, writing in the Journal of the Chinese Medical Association warned: “Preoccupied with the diagnosis of SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory syndrome) in a SARS outbreak, doctors tend to overlook other endemic diseases, such as tuberculosis.”

Perhaps Wong’s warning should be listened to. The present and ongoing COVID-19- pandemic, did not occur in a vacuum. By December of 2018, Liu et al., in a large multi-center study, proclaimed tuberculosis to be an epidemic throughout China, which still simmers on in a country with the second largest burden of that disease in the world ̶ a disease which also often begins with flu-like symptoms, and a disease whose bacilli are laden with RNA bacterial viruses called mycobacteriophages.

It was a non-virus in 1918 too

Demographers at UC Berkeley (Noymer and Garenne, Population Development Review 2000) claim tuberculosis was behind the many deaths in the 1918 Great Influenza Pandemic was specifically based upon the well-known concept that the secondary bacterial infections that cropped up in 1918 were common in TB-infected lungs.

And in Hiroshi Nishiura’s study (2012) not only was TB shown to be associated with influenza death, but there was no influenza death among controls without TB. Investigator Nishiura later concluded: “Should a highly fatal influenza pandemic occur in the future, testing the role of TB in characterizing the risk of death would be extremely useful in minimizing the disaster…”

But was Nishiura being listened to and learned from? Apparently not. Fast forward, Wuhan, China (2019-2020):

The chronological timetable of the present Wuhan “viral” pandemic suggests nothing “new” or “novel”. The coronavirus outbreak started in December 2019, first identified in Wuhan, after 41 people presented with pneumonia of no clear cause. The Wuhan winter is from December to February. Yang’s Wuhan study from 2004 to 2013, described the annual TB surge in Wuhan as being fueled by increased transmission in the winter, peaking in March, with a second smaller peak in September. Among the conditions Yang attributed to the increased transmission of TB in the winter was indoor crowding, subsequent vitamin D deficiency, and even air pollution.

The increasingly severe air pollution in Wuhan, powered by the influx of foreign companies and the increased use of incineration for waste disposal, resulted in a visible haze so thick that it reduced peripheral vision as far back as June of 2012 ̶ a haze with inhalable particulate matter, highest in the winter, which according to Yang, was of a particulate size able to harbor Mycobacterium tuberculosis and related mycobacteria. Why is this important?

Pigs

Wuhan’s economy was on fire. With it came a greatly increased demand for poultry and swine, two staples of the Chinese diet, along with the expansion of farms to raise them and the inevitable tons of waste that this brought. Even as far back as 2015, there were five major waste incineration plants in Wuhan, with many more scheduled to be built.

That was just the beginning. By July, 2018, fourteen large pig breeding farms in Wuhan, with a combined annual pig production of 1.5 million pigs pooled investments with the intent to slaughter 2 million pigs per year. China alone accounted for more than half of the world’s pig population. That is until another purported virus (African swine fever) spread throughout China which had no cure and a near zero survival rate for infected pigs, and which, by August 2019 virtually wiped out 40% of China’s entire pig population, including those in Wuhan.

Essentially one-quarter of the world’s pigs died in one year, and just before the latest coronavirus outbreak. China then did what it had to do and began to cull thousands of pigs to control the outbreak they claimed to be caused by the African swine fever outbreak in 2018.

But how many dead animals, including those in Wuhan were buried and how many incinerated are open questions. Burning pigs and pig excrement was a sure recipe for visible haze.

The Chinese government soon came up with incentive programs for livestock farmers to sell their manure to use as fertilizer, which was only marginally successful.

During a study from 1953 to 1968 (Tubercle 1970) in the UK, an astonishing 81% of pigs were found to harbor Mycobacterium avium, or fowl tuberculosis. As reported by some workers, M. avium isolates from swine represent a major threat to human beings. The similarity pre-programmed (IS1245 RFLP) patterns of the human and porcine isolates indicates close genetic relatedness, suggesting that M. avium or fowl tuberculosis is transmitted between pigs and humans.

Fort Funston 1918, Kansas USA

Similar events occurred at Fort Funston in Kansas circa 1918, thought by many to be the birthplace of the onset of the Great Influenza Pandemic of 1918.

It was only with industrial development that the US tuberculosis epidemic traveled to the Midwest and Kansas, the very American Midwest where the 1918-flu pandemic of unknown origin hit, in rural Haskell county, Kansas, in the midst of an infectious pig slaughter of undiscovered cause, a few hundred miles from Camp Funston, today Fort Riley.

It had to be more than a coincidence that by the autumn of 1918 thousands of Midwest pigs died, seemingly from the same flu-like illness and in the same Haskell County location in which the worst human pandemic in history, which would kill between 50 and 100 million people, was about to begin.

US Inspector and veterinarian J.S. Koen, for lack of another term, and with no evidence other than a hunch, quickly called this unknown disease in pigs “swine influenza,” even as it killed pig after pig.

Pigs were dying in 1918 and in 2019-20

That thousands of pigs died in the Autumn of 1918 was problematic in that bird or fowl TB, also called Avian tuberculosis or Mycobacterium avium, routinely infects birds as well as hogs and sometimes cattle –but could, under the right conditions, also infect man. So, pigs had involuntarily become the living laboratory thru which three of the main types of tuberculosis (human, cow and fowl) could mutate through the genetic exchange by their viral mycobacteriophages, much in the same fashion as has been attributed to the influenza and coronavirus. (A bacteriophage is a virus that parasitizes a bacterium by infecting it and reproducing inside it.) But, in so far as 1918 was concerned, the stage was set for disaster.

Airborne TB

Unknown at the time, but pertinent since Kansas lies squarely in America’s “dustbowl,’’ were the results of a previous European experiment wherein guinea pigs exposed to organisms like Avian tuberculosis got little or no lung disease. However, when these mycobacteria were placed in dust aerosols with particulate matter, guinea pigs came down with progressive, fatal lung disease, not unlike what was occurring in the pandemic of 1918 as well as a prominent factor in the present Wuhan air pollution with its particulate matter haze.

Burning animal waste

Ft. Riley, Kansas was a sprawling establishment housing 26,000 men and encompassing an entire camp, Camp Funston. Within that camp, thousands of horses, hogs, mules and chickens produced in excess of a stifling nine tons of manure each month. And the accepted method for its disposal was to burn it, even against driving wind.

State Veterinarian W.J. Butler would report at the 28th Meeting of the United States Live Stock Sanitary Association: “I consider contaminated manure and stagnant water the most important factors in the spread and propagation of tuberculosis.” Wang’s recent JAMA study suggested that Coronavirus may spread fastest on cruise ships and in hospitals where workers re-use gear contaminated with feces to try to conserve supplies.

And so, on Saturday, the 9th of March, 1918, a month which just happened to coincide with the annual peak surge for tuberculosis in Wuhan, China, a threatening black sky forecast the coming of a major dust storm. When this storm combined with the ashes of over 9 tons of burning manure, a stinking, stinging yellow haze resulted.

The sun was said to have gone black in Kansas that day in 1918. Two days later, on March 11th, company cook Albert Gitchell reported to the Funston infirmary saying he had “a bad cold” with flu-like symptoms. Among his symptoms were a headache, a sore throat, muscle aches, chills and fever. He also reported cleaning pig pens on March 4th, one week before feeling sick. Gitchell would never recover from this, his last illness. And by noon of March 4th, one hundred men joined him at the Army infirmary he had walked into. Within a month one-thousand men were sick and approximately 50 dead. Camp Funston was having a deadly epidemic.

These deaths were highly unusual, but nothing like what would return in the fall, when the disease would come back with a vengeance, seeming to gain strength through human passage. Camp Funston in March, Camp Devens in September (a month that coincides with the second annual TB peak surge in Wuhan), then across the country and the world, leaving an estimated 50-100 million dead globally, at least 600,000 to a million of them American, in the span of less than a year –the most destructive plague that mankind had ever witnessed.

Implications of mistaking a mycobacterial disease for a viral disease

What are the implications of mistaking a mycobacterial disease for a viral disease? While an anxiety-filled world is losing sleep over a “coronavirus” that has resulted in the deaths of less than 2000 people, a mycobacterium called tuberculosis is encircling the planet that is killing 1.7 million people a year, and is once again, the single largest cause of infectious death on the globe. And that does not even include morbidity and mortality coming from its closely related Mycobacterium avium or fowl tuberculosis, for which, although there is treatment, we have yet to develop ideal drugs to treat.

Moreover, the preferred form of both of these pathogens, once inside the body, is their tiny, hard to diagnose viral-like cell-wall-deficient (CWD) mycobacterial forms, which require special stains and special culture media, unavailable at most diagnostic centers. This leaves a situation, in which Mycobacterium avium and its cell-wall-deficient forms, highly implicated here in the present pandemic, are being picked up, according to Mattman, only 16% of the time through traditional methods.

If we are not looking or unable to look diagnostically for the underlying Wuhan pathogen, then how can we truly treat it effectively?

In 1933 researchers claimed they had first discovered human influenza “virus.” So, what was the flu virus of 1918?

Historically, in 1892 the flu was originally named Mycobacterium influenzae because it resembled tuberculosis. In the lab, both of these pathogenic organisms stain similarly on a lab slide. Staining is one method of identifying types of bacteria. Also, it was eventually found that Mycobacterium influenzae and Mycobacterium tuberculosis have similar genetic profiles.