Morgellons - Figments of our Imagination?

Thousands of people around the world say they have a disease that causes mysterious fibers to sprout painfully through the skin, and they've given it a name. The spread of 'Morgellons disease' could be Internet hysteria, or it could be an emerging illness demanding our attention.

By Brigid Schulte

Sunday, January 20, 2008; W10

WashingtonPost.com

Sue Laws remembers the night it began. It was October 2004, and she'd been working in the basement home office of her Gaithersburg brick rambler where she helps her husband run their tree business. She was sitting at her computer getting the payroll out, when all of a sudden she felt as if she were being attacked by bees. The itching and stinging on her back was so intense that she screamed for her husband, Tom. He bounded downstairs and lifted her shirt, but he couldn't see anything biting her. She insisted something must be. To prove there was nothing there, he stuck strips of thick packing tape to her back and ripped them off. Then they took the magnifying eyepiece that Tom, an arborist, uses to examine leaves for fungus and blight and peered at the tape. "That's when we saw them. It was covered with these little red fibers," Sue recalls. She'd never seen anything like them. And she had no idea where they came from. "You automatically think clothing. But I wasn't wearing anything red."

Sue Laws remembers the night it began. It was October 2004, and she'd been working in the basement home office of her Gaithersburg brick rambler where she helps her husband run their tree business. She was sitting at her computer getting the payroll out, when all of a sudden she felt as if she were being attacked by bees. The itching and stinging on her back was so intense that she screamed for her husband, Tom. He bounded downstairs and lifted her shirt, but he couldn't see anything biting her. She insisted something must be. To prove there was nothing there, he stuck strips of thick packing tape to her back and ripped them off. Then they took the magnifying eyepiece that Tom, an arborist, uses to examine leaves for fungus and blight and peered at the tape. "That's when we saw them. It was covered with these little red fibers," Sue recalls. She'd never seen anything like them. And she had no idea where they came from. "You automatically think clothing. But I wasn't wearing anything red."

Over the next month, Sue's itching intensified. Every night, she says, it felt as if thousands of tiny bugs were crawling under her skin, stinging and biting. She became unable to sleep at night. She left the lights on, because the crawling seemed to be worse in the dark. Thinking it might have been a flea infestation, Sue and Tom pulled up all the carpets in the house. Thinking perhaps it was mold, they tore off the wallpaper. They sanded and stained the bare floors, and then Tom called an exterminator.

Over the next month, Sue's itching intensified. Every night, she says, it felt as if thousands of tiny bugs were crawling under her skin, stinging and biting. She became unable to sleep at night. She left the lights on, because the crawling seemed to be worse in the dark. Thinking it might have been a flea infestation, Sue and Tom pulled up all the carpets in the house. Thinking perhaps it was mold, they tore off the wallpaper. They sanded and stained the bare floors, and then Tom called an exterminator.

Every morning, Sue says, she found little black specks all over her side of the bed. Then she discovered droplets of blood where the specks appeared to be coming out of her skin. "I looked like I had paper cuts all over," she says. She began washing the sheets in ammonia every day. Next, her chest, neck, face, back, arms and legs broke out in painful, red gelatinous lesions that never seemed to heal. To get some relief, she stayed in the shower for hours. She bathed in vinegar and sea salt and doused her body with baby powder. Nothing really helped.

Her joints began to ache. She lost all her energy and became forgetful. She says she would comb her hair, and tangled clumps of what looked like hair, fibers, dust and skin tissue would fall out. Then, she says, her actual hair began to fall out and her teeth began to rot. She refused to let anyone in the house and stopped going out. She didn't know what she had, but she was afraid she might be contagious.

One day, she says, a pink worm came out of one of her eyeballs and she coughed up a springtail fly. "That's when I thought, 'I'm really going to kill myself,'" she says.

Sue visited a dermatologist, who said he didn't know what was wrong. In time, Sue, 51, came across a condition on the Internet that sounded exactly like her own, and joined 11,036 others from the United States and around the world who, as of earlier this month, had registered on a Web site as sufferers of what they say is a strange new debilitating illness. Some call it the "fiber disease," but most refer to it as Morgellons, a name taken from a similar condition of children wasting away with "harsh hairs" described in the 17th century. A frustrated mother, Mary Leitao, then living in South Carolina, happened upon the description in an old medical history book in 2002 after doctors didn't believe her when she told them that her son had fibers growing out of his lip.

The catalogue of symptoms for Morgellons includes crawling, biting and stinging sensations, granules, itching, threads or black speck-like materials on or beneath the skin, skin lesions, fatigue, joint pain and the presence of blue, red, green, clear or white fibers. Other symptoms supposedly include what some sufferers politely refer to as "neurological effects," such as mental confusion, short-term memory loss -- and hallucinations such as, possibly, Sue's descriptions of the pink worm and springtail fly.

Pam Winkler, 42, says she was once the perfect suburban wife in Bel Air, Md., with a large colonial-style home, two beautiful children and a picture-perfect marriage to her childhood sweetheart. She became so delusional with Morgellons, she says, that she twice wound up in the psychiatric ward against her will and was put on antipsychotic medication. (Ironically, pimozide, an antipsychotic medication she was prescribed, also works as an antimicrobial and relieves itching.) For two years, she says, she's been unable to work, to sleep at night or to do much of anything. She says neither her husband, from whom she is getting divorced and who has custody of their children, nor her other family members believe her. She says they tell her that she needs help with cocaine addiction and just wants attention. Winkler says she became hooked on cocaine because she was so fatigued with Morgellons that she couldn't wake up. Now, she takes Provigil, a narcolepsy medication, to stay awake.

At her worst, she was locked up in a state mental hospital in North Carolina with what she describes as lesions covering her body and black fibers and specks coming out her nose. Doctors there said her open sores were self-inflicted, caused by her constant scratching. She recalls crying in misery to her husband. "You know me. I'm a shallow person. I'm vain. Do you think I'm doing this to get attention? If I wanted attention, I wouldn't look this skanky. I'd get boobs."

Many Morgellons sufferers report they have lost their jobs, their homes, their spouses and even had their children taken away because of the disease.

Lalani Duval, a 47-year-old cosmetologist who lives in Fort Washington, hasn't let her grandchildren near her for more than a year since her incessant itching started. She refuses to visit her mother for fear she'll give her and the rest of the family whatever she has. Her relatives bring her plates of food after holiday meals. "I've picked up a gun three times and put it to my head thinking I can't take it anymore," she says. "This stuff is coming out of my eyes. I vacuum my bed six times a night. This is a living hell."

Whatever it is -- and most doctors believe it's purely delusional -- Morgellons has become a grass-roots Web phenomenon. Google it, and nearly 162,000 references show up, many of them chock-full of vivid color photographs of what people claim are strange, colorful fibers growing under their skin. Several other sufferers have taken graphic videos of themselves poking with tweezers at what appear to be fiber-entangled lesions and then posted them on YouTube. Long online discussions ramble on about the latest conspiracy theories that cause the disease -- poisonous chemicals produced by the government and spread by jet contrails, so-called chem trails; aliens; artificially intelligent nanotechnology; genetic engineering; or a government bioweapon gone awry. Others debate the latest expensive cure-alls -- antibiotics, antifungal creams, vitamin supplements, liquid silver, food-grade diatomaceous earth, deworming medication meant for cattle.

But look on the official American Academy of Dermatology Web site, and Morgellons isn't there. The skin afflictions starting with M jump from "Molluscum contagiosum" to "Mucocutaneous candidiasis." Ditto on the Infectious Diseases Society of America. A search for Morgellons on the National Institutes of Health site returns "no pages found." There is only one study of Morgellons in a peer-reviewed medical journal, the holy grail for Western medicine.

Jeffrey Meffert, an associate professor of dermatology at the University of Texas in San Antonio and a member of the American Academy of Dermatology, gives presentations to the medical community debunking Morgellons. It's not that people aren't suffering; they are, he says. It's just that he thinks they have something else, such as scabies or an eczema-like skin condition called prurigo nodularis that's little understood and for which there is no good treatment. And the fibers, he says, are easy to explain.

"People with very itchy skin have scabs, which ooze and tend to pick up threads from the environment, from dogs, cats, air filters, car upholstery, carpet," he says. "Any fibers that I have ever been presented with by one of my patients have always been textile fibers."

Despite the extreme skepticism in mainstream medical circles, the federal government is now taking Morgellons seriously because of pressure from sufferers and the Morgellons Research Foundation, the nonprofit organization that Mary Leitao founded in 2002 and now runs out of her house in Pennsylvania. The group is funded through contributions -- $29,649 in 2006, according to its Web site. And it uses much of the money to promote public awareness and provide small research grants.

In recent years, self-described sufferers clicked on the foundation Web site and sent thousands of form letters to members of Congress. More than 40 members from both parties, including presidential candidates Sens. Hillary Rodham Clinton, Barack Obama and John McCain, leaned on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the nation's public health watchdog, to look into the disease. Sen. Barbara Boxer wrote seven times.

As a result, the CDC has budgeted nearly $1 million in the next two years for Morgellons research and is undertaking the first major epidemiological study of what it is calling an "unexplained dermopathy." Sen. Tom Harkin inserted language in a Labor Health and Human Services bill, later vetoed by President Bush, urging the CDC to continue the Morgellons investigation and "as quickly as possible to plan and begin this important research."

The CDC has contracted with Kaiser-Permanente to begin the study early this year in California. It's hoping to send the fibers collected from patients to the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology in Washington for analysis.

"No one is denying or trying to downplay that these people have something going on. It's just what is the something?" says Mark Eberhard, division director for parasitic disease at the CDC and part of a 12-member task force investigating Morgellons. He says he began to hear of similar cases when he was in graduate school 35 years ago. "This is a topic that people in the medical community have not wanted to engage on because it's very complex," he says. "There's not a clear direction forward . . . This is why we need to be very open. I'm a parasitologist, but maybe there's a virus or bacteria. We need to start with a very broad approach."

The task force will include psychiatrists. "Some of this may even be a mental condition," Eberhard says. "That's why we've been suggesting that there has to be not only a physical but mental evaluation as well as part of any study."

Sue had been going to see Praveen Gupta , a family practice physician in Rockville, for regular physicals for 14 years. He would get after her for drinking too much coffee, sometimes as many as 30 cups a day, he noted in his records. (Sue says she has never had more than five cups a day.) And he tried to get her to cut back on her three-pack-a-day smoking habit. He knew her husband and four children and thought they were all rather nice. And he knew she'd had her share of tragedies, including a son who'd been diagnosed with a malignant brain tumor. But nothing prepared him for her call in late November 2004.

He jotted notes in her medical chart: "She says she's coughing up bugs and worms." She complained of lesions all over her neck, chest, arms and legs that wouldn't heal and itching that would not end and worsened at night. She couldn't sleep. She couldn't think straight. And she said she saw fibers -- strange red, blue and black fibers -- coming out of her skin. Alarmed, he made an appointment for her to come see him that December. But when Sue came in, Gupta says, he found nothing.

"Just a generalized rash, which she could have scratched herself. Nothing out of the ordinary," Gupta says. "It was very bizarre. She brought a sample in. It didn't look like worms, that's for sure. It didn't look like any parasites, that's for sure. It looked like it could have been from the carpet. It could have been dog or cat hair, for all I know."

He sent Sue to an infectious disease specialist at Washington Hospital Center in the District. The lab analyzed her samples and found them to be "amorphous fibers and debris." The overall impression: It was all in her head. She was suffering from what doctors call "delusions of parasitosis." And a big part of the diagnosis was the fact that she'd brought in a sample. That's called the "matchbox" or "Ziploc" sign, named for the containers people tend to use to bring in samples of what they say ails them. Doctors disproportionately diagnose middle-aged women with this condition. Leitao says that three times as many women as men have registered on her Web site as Morgellons sufferers. She speculates that males may be less inclined to register.

Once Gupta received Sue's test results, he called her with the news. He told her that what she needed was not antibiotics, but a psychiatrist. "There are people who hurt themselves, and they can't help themselves," Gupta says. "It's not an unusual situation. These people keep going to doctors -- they doctor-shop -- until they find the answer they want. It's a psychiatric condition that's very difficult to treat."

Sue never saw Gupta again.

Instead, she sought out more than eight doctors and specialists, not because she's crazy, she says, but because she was in agony. All she wanted was relief. She gave her physicians permission to discuss her case and records with a reporter. One doctor told her she had athlete's foot. Another said shingles. Another scabies. One treated her with antibiotics used for Lyme disease, which eased her itching a bit. One told her to go to a movie to get her mind off it. Martin Wolfe, a parasitologist at Traveler's Medical Service in downtown Washington, thought Sue was imagining things when she went to see him. She brought in fiber samples, which he believed fit the delusional diagnosis. Wolfe said he did not see any fibers in her lesions. But Sue complained that Wolfe, like the other doctors she sought out, declined to examine her skin with a microscope.

"In my experience, there's no precedent for this sort of thing happening to human beings, so it's hard to imagine that this is something that's real," Wolfe says, referring to the reports of subcutaneous fibers. Still, he mentions a number of diseases now being tracked that medicine didn't recognize initially, including Rift Valley fever, West Nile virus, tularemia and Ebola virus.

"Is it possible this is something new?" he says. "I can't say it's utterly impossible. But in my mind, it's very improbable."

Phuong Trinh, an infectious disease specialist in Silver Spring, took the samples Sue brought him in little jars. "They looked like dust balls," he says, "things you would see in the rug or the stuff you'd get from your vacuum cleaner." He checked her for every known parasite but found nothing. He, too, told her she was delusional.

"I was labeled crazy," Sue says. "But I was desperate, and no one was listening to me. I was acting delusional when I saw some of these doctors. I was going out of my mind. It's so horrible and bizarre, who could believe it in the world?"

There are a lot of reasons why skin itches. Search the online Merck Manual, the doctor's bible, for "itch or itching," and more than 500 conditions pop up. According to Wrongdiagnosis.com, a clearinghouse of medical information on the Web culled from existing medical literature, there are 703 conditions that can make the skin itch, including diabetes, anemia and iron deficiency, in addition to common disorders such as allergies, viruses such as chicken pox and insect bites. "Swimmer's itch" is the result of an allergic reaction to the larvae of freshwater snails. New research has found that too much calcium in the blood can make the skin itch and that some dental sealants used for fillings can trigger intense itching. Additionally, the site lists 1,742 medications that can cause itching. Those include legal substances such as aspirin, Advil, penicillin and codeine, as well as illegal ones such as cocaine and heroin. "Coke mites" is what the cocaine-induced itching is commonly called, though there are no actual bugs associated with it. Drug or alcohol withdrawal can also cause intense itching. As can the power of suggestion.

And the skin itself is a virtual hothouse of potential infection. Researchers have found that our skin is host to at least 182 species of bacteria, many previously unknown.

So, would it be outside the realm of possibility that these fibers, rather than being delusions, could be something medicine has not seen before? Western medicine has been guilty of closed-mindedness in the past. There is even a name for it: the Semmelweis Reflex, the immediate dismissal of new scientific information without thought or examination. It was named for a 19th-century Hungarian physician who was roundly vilified by his colleagues when he asserted that the often fatal childbed fever could be wiped out if doctors washed their hands in a chlorine solution. He was right. The same knee-jerk rejection of a new idea was true for the bacteria H. pylori, which doctors, researchers and scientists refused to believe was the source of stomach ulcers until the doctor who'd made the connection swallowed some himself to prove it.

And could some diseases, rather than being all in the head, involve both mind and body? Medical researchers are beginning to study the potential link between schizophrenia, a disease of the mind, and exposure to infection in the womb. At the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., doctors are beginning to discover how imprecise a diagnosis of "delusions of parasitosis" can be. In the past five years, 175 people have been admitted to the clinic with that diagnosis. After thorough evaluations, however, with doctors taking the time to search for underlying problems, only half of those patients left the clinic with that diagnosis intact. Doctors found a very real cause of the itching in the other half. The Mayo Clinic is the only other organization in mainstream medicine, outside of the CDC, to include information about Morgellons in its list of human illnesses.

Michael Bostwick, an associate professor of psychiatry at Mayo, says he told a gathering of dermatologists not long ago that they should stop running from Morgellons patients. "I got hissed out of the room," he says. "I think the best thing to say is that people are having an experience, and it's not explained. And people look for explanations. Separating the narrative truth, the stories people tell to explain what's going on, from the biological truth seems to be the challenge of this condition . . . The skin and the brain are derived from the same tissue. It seems completely plausible to me that brain and body and skin could all be related."

Robert Bransfield is a New Jersey psychiatrist who studies the connection between infection and mental illness. He is also one of the handful of physicians and researchers who volunteer as unpaid advisers to the Morgellons Research Foundation and who serve on its medical advisory board. "This isn't delusional," Bransfield says. "Delusions are quite variable. So, one person might have a delusion that the FBI is sending out messages to his dentures. Someone else has a delusion that their next-door neighbor is stealing their mail. But the people who have Morgellons all describe it in the same way. It doesn't have the variability you would see in delusions."

And what of mass hysteria? Could Morgellons be, in a very real sense, nothing more than an Internet virus that has taken hold in susceptible minds? "I do see suggestion with the Internet, but it's hard to explain it on that alone," Bransfield says. "You can see the fibers. The fibers can't be mass hysteria. You see people describe this who don't have a computer," he says. "It's puzzling. It's hard to make sense out of it. But it's there. "

Before Sue got sick, friends and family members say she was a high-energy, Type-A person, especially when revved on caffeine. She was the kind of person who, when she wanted to paint the house that day, would paint it, with two coats. Her husband, Tom, says he barely recognized the woman who began spending hours every day sitting on a heating pad in a hard, wooden chair in her kitchen, and spending her nights in the same chair, staring into the darkness.

When she wasn't sitting catatonically in the chair, desperate but unable to sleep, Sue was at the kitchen counter peering at her own open sores through a microscope she had purchased on the Internet or taking digital photographs of anything that came out of her. And when she wasn't doing those things, she was surfing the Web for answers. At one point, she was convinced that she had T. cruzi, a parasite that causes Latin American sleeping sickness. Her dermatologist had told her to contact NIH. Sue says a researcher there gave her information on Morgellons Web sites. She went to the MRF Web site and found that she was experiencing every symptom listed -- fibers, crawling sensations on the skin, brain fog, chronic fatigue, joint pain and more. Now, she believed, she had a diagnosis. What she needed was a cure.

The doctors may have dismissed her symptoms, but, unlike with so many others who say they have Morgellons, Sue's family believed her. When her Dino-Lite microscope broke from overuse, Tom bought her a new, more powerful Accu-Scope for Christmas. He took her to every doctor's appointment, even counseling her to slow down when she spoke because, when she tried to get everything out in the five minutes a doctor allotted her, she sounded nuts.

"Honestly, I didn't know what to think about the fibers," Tom says. "I knew they shouldn't be there. But they weren't coming off any carpet. I'd watch her pull some nasty, knotty thing out of her arm. She'd work at it and work at it and work at it and pull it out. Now, that ain't right.

"To be honest, if I did not know my wife, I would think she's crazy. But I know my wife. I know she's not crazy. If you felt like a bee was stinging you every day for two years, could you take it? I wouldn't be able to. I'd be out in front of the train that goes behind my house every day."

Still, there are some days Tom can't take it. "I'm not a saint," he says. On those days, he goes out and chops wood.

Sue's daughter Tina moved back home in July 2005 to help care for her brother when his brain cancer returned. When Tina walked in the door for the first time, she remembers, Sue was bald and covered in open sores. "She looked like a leper." Tina worried that the stress of Josh's fatal condition had pushed her mother over the edge. "If you look at your skin through a microscope 24 hours a day, you're going to go crazy," Tina says. "But then I took a look. I saw bugs and things that should not be there coming out of her skin. That changed everything." The mainstream medical community, which thinks Sue is delusional, would say that neither Tom nor Tina saw anything, but rather were drawn in by the power of Sue's fantasy. They call it folie ¿ deux, "madness of two," or ¿ trois, ¿ famille, ¿ plusieurs or whatever number is required to explain the phenomenon.

Family members say they began to find blue and red fibers on Josh's skull, where his brain surgery incision ran. They asked the surgeon about the color of stitches he used. When he said they were black, they became convinced that Josh, too, had Morgellons. Josh broke out in lesions all over his chest and back and was driven to distraction by itching. Sue says the chemotherapy eventually killed Josh's nerve endings, and he could no longer feel the itching. When Josh died in 2006 at age 22, he was covered in fibers and lesions, Sue says. The funeral home called to ask if any special precautions should be taken when handling Josh's body. "Is there anything we should know?" Sue and other family members recall them asking. "We've never seen anything like this."

Randy Wymore, a molecular biologist who studies gene expression in cancer and heart disease at Oklahoma State University, was probably the first scientist to look at what doctors and dermatologists typically discard as bits of fluff and dust. In the spring of 2005, a student in his second year of cardiac pharmacology class asked Wymore a question about muscle fibers. On a Friday, searching the Web for answers, he hit upon some fiber disease and Morgellons sites. "It sounded totally crazy," he says. But, over the weekend, he kept thinking about the fibers. On Monday, he figured it should be easy enough to determine if the fibers really are from textiles, as doctors say, or from the body, as sufferers contend. So he e-mailed some of the people who'd posted photos of their fibers asking for samples to analyze.

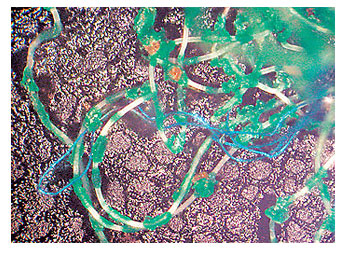

He was expecting to get bags filled with dirt, ants, flies or cotton threads. Instead, within 48 hours, he started getting packages from Texas, Washington, Florida, California, Pennsylvania and other states. What he saw was surprising. "Even though they were coming from very different places, they all looked very similar to one another," Wymore says. "The texture and shades -- a cobalt blue, red fibers that are almost a magenta color -- are very, very similar." And they all autofluoresced, or glowed, in certain light. He picked threads out of bluejeans, fuzz from the carpet, even pepper flakes and compared them to the fibers. He became convinced that the fibers were something entirely different.

With a colleague, Rhonda Casey, a pediatrician, and a $4,000 grant from the Morgellons Research Foundation, Wymore got fresh fiber samples from 20 Morgellons patients. He brought them to fiber analysts at the Tulsa Police Department's forensic lab. The red and blue fibers did not match any of some 900 commercially available textiles in its database. They were not modified rayon, nylon, cotton or anything previously catalogued. Then forensic scientists tried to burn one of the fibers, heating it to 700 degrees Fahrenheit, to determine if it matched any of 85,000 known organic compounds. Again, nothing matched. And the heat, which typically vaporizes any organic material, did nothing to the blue fiber. "We were able to reach in with a tweezers and pick it up," Wymore says. So, he is pretty clear about what the fibers aren't. "But I don't have the foggiest idea what they are."

Wymore has since had a falling out with Leitao and other MRF board members over management and funding issues and has started his own foundation at Oklahoma State to raise funds and search for a cure.

Ahmed Kilani, an infectious disease microbiologist who runs Clongen Laboratories in Germantown, also thought he could figure out the Morgellons mystery fairly quickly. In late 2006, out of the blue, he began getting phone calls and e-mails from Morgellons patients. He took pity on them. "They suffer so much," he says. He contacted Leitao at the MRF and started collecting fiber samples. Under the microscope, they looked just like the fuzz from his office carpet. Still, he dressed in a biohazard suit and tested for leishmaniasis, or "Baghdad boil," a nasty disease of lesions transmitted by sand flies. No match. He spent thousands of dollars building assays to test for protozoal infections and fungal diseases. "It was like chasing ghosts," Kilani says. He began thinking the fibers might be the feeding tubes of fungal spores. He amplified the fungal DNA from the fibers, but it didn't match anything published in medical literature. "Unfortunately, this turned out to be more difficult than I thought. I still do not have an answer," says Kilani, who is now part of the MRF scientific advisory board. The MRF has paid $2,000 for lab chemicals for his work.

At about the same time, Leitao, who was trained as a biologist and worked as an electron microscopist; along with Ginger Savely, a nurse practitioner; and Raphael Stricker, a hematologist, published a paper in the American Journal of Clinical Dermatology reporting that 79 out of 80 Morgellons patients they studied also were infected with Borrelia burgdorferi, the tick-borne bacteria that cause Lyme disease. Savely and Stricker, who practice medicine in San Francisco, specialize in treating patients with chronic Lyme disease with high-dose antibiotics -- a controversial condition and treatment that many mainstream doctors discount. In interviews, Savely and Leitao hypothesized that perhaps Lyme disease or other infections weakened the body's immune system, which allowed Morgellons to take hold. In their paper, they theorized that the fibers appeared to be some type of cellulose. And they noted that Morgellons infections seemed to take off after patients had some kind of contact with soil or animal waste products.

That's the only thing that Dona Forehand, 58, can think might have happened to her. She remembers being out in her Lynchburg, Va., home gardening all day in September 2005, getting ready to show her house for the city's Garden Day. That night, she woke up screaming with blisters in a circle on the crown of her head. Over the months, sand-like granules kept falling from her scalp, gaping lesions crisscrossed with a patchwork of fibers opened on the top of her skull, and she itched like mad. She had been prominent in nearly every charity organization in the city, but she dropped out of sight. For more than a year, she did little but try to pick the fibers out of her head. Eight hours a day, she says. Every day. She went to see 15 specialists. They all told her she was nuts and that the sores were self-inflicted. "The story sounds like it's from the 'Twilight Zone,'" Dona says. "I would rather have gone in to see a doctor and, honest to God, have somebody say, 'You have breast cancer.' I'd be like, 'Okay, we know what to do with that.' But to go in with a disease that doctors don't know what it is, don't believe in it, can't explain. There's no reason. There's no cure. I would much rather have had cancer. I know that sounds crazy, but it was like, give me something I can work with here."

Dona's husband, Jimmy, a real estate developer, didn't believe her either, at first. "I thought she was having some hallucinations," he says. "I felt it was something she could control herself." But that wasn't like Dona, he says. Dona is a former Miss Virginia. She's smart, energetic and level-headed. "She lost all her energy. She slept a lot. It just wasn't Dona. It just wasn't the girl that I married."

Then Dona learned about Savely's work from an Internet search last January. "I was told these two were the only doctors on the planet who take Morgellons seriously," she says. It was all she could do to pull herself together and fly out to see them last March. Jimmy went along and finally became a believer. "At first, I still thought if she would stop her scratching, it would heal up and go away," he says. The doctors convinced him otherwise. "'Oh, no,' they said. 'This is a real, real thing.'"

Dona now flies out to California every few months for treatment with cocktails of antibiotics and pays for regular phone appointments with Savely. She says she's feeling well enough to get out occasionally and play golf, though she wears wigs because the heavy antibiotic doses have twice made her lose her hair. "There are people who have committed suicide because of this disease," she says. "I think if I had not found her, I would have."

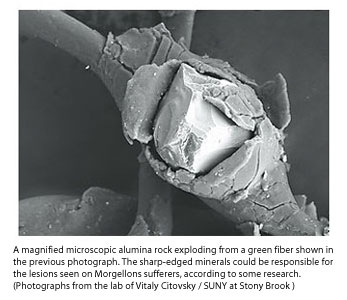

With their new theory that the fibers could be made of some kind of cellulose, Savely and Stricker, both of whom are on the MRF medical advisory board, contacted Vitaly Citovsky, a plant biologist at the State University of New York at Stony Brook. Stricker suspected that agrobacteria, common bacteria found just about everywhere that cause tumorous crown galls to form in trees, were somehow related to Morgellons because agrobacteria like to bind with cellulose. Citovsky studies agrobacteria and its use in genetically modifying plants. It was his lab that showed that agrobacteria can genetically transform any organism, including human cells, by transferring DNA into it.

Citovsky prefaced his interview for this article with, "I'm a normal scientist." He says he was interested in a basic scientific puzzle. "At the time I became involved, I knew nothing of the controversy that surrounds this thing. I didn't know that half the people were crazy. Ninety percent of the stuff on the Internet is absolute lunacy. Government conspiracies, nanotechnology," Citovsky says. "People e-mail me that they have wasps coming out of their skull." Citovsky hypothesizes that Morgellons, like syphilis and other infections, can act on the central nervous system and brain and cause hallucinations.

For his study, funded with $3,400 from MRF, Citovsky tested the skin of five people who believed they had Morgellons and a control group of five people, including himself, who did not. He found agrobacteria in only the Morgellons samples. Then he studied the fibers. Many of them, he says, appear to be polysaccharides, or long sugar molecules, which could be cellulose. And he found they contain traces of metal, such as aluminum. But, like Stricker, Savely and Wymore, he won't be certain what the fibers are until their DNA is tested, an expensive process that the MRF is unable to fund. "To me, it indicates that there is something there. It's not like someone picked up lint from their dryer. But that's all we have," says Citovsky, now a member of the MRF's scientific advisory board.

William Harvey, 70, who serves as chairman of the MRF board, has taken those theories one step farther. He says he became interested in Morgellons research after successfully battling chronic fatigue syndrome and made it his mission to find cures for such unexplained illnesses.

He wouldn't be specific, explaining that he first wants the results of his research to appear in a top-notch, peer-reviewed journal such as the Lancet. "This may be the story of the century," he says. A semi-retired doctor in Colorado Springs who spent most of his career working in space medicine for the Johnson Space Center, Harvey says he may have found not only why Morgellons patients would both scratch and act strange, but also what could be the "genesis of probably most chronic human illnesses," such as autism, obesity, chronic fatigue and bipolar disorder.

It all boils down to this: mutant worms.

Harvey hypothesizes that a type of nematode, a wormlike parasite that lives in the soil as well as in the guts or lungs of about half the animals on the planet, mutated somewhere in the 1970s in Southeast Asia and jumped from animals to humans. The parasite is easily spread through the fecal-oral route if someone, for example, is out working in the garden, fails to wash his or her hands thoroughly and then eats an orange. Or it gets into the lungs by inhaling sputum or by kissing. The worm then takes up residence in the colon, Harvey theorizes, and the body's immune system holds it in check.

But when the immune system falters, the worms swarm in the body. That's what happens, Harvey hypothesizes, after a human is infected with a strain of bacteria first reported in 1986, Chlamydophila pneumonia. These bacteria like to live in immune cells, Harvey says, and they feast on those cells' energy. With the host's immune system compromised, the mutant nematodes begin reproducing exponentially, Harvey suspects. They burrow a hole in the wall of the colon, then usually travel at night through the bloodstream or the lymphatic system or crawl in hordes between the layers of the skin, like other species of nematodes are known to do, to the parts of the body with the most blood flow: the face, head and nose. There, a cranial nerve leads right into the brain. A pileup of worms could jam blood and oxygen flow to the brain, Harvey says. "That may explain the psychological symptoms," including the hallucinations, he says.

It may explain why Pam Winkler took herself to the emergency room recently. She said that a huge bump had appeared on the side of her skull in the middle of the night. By morning, she said, the bump was gone, but she could feel crawling all over her face. She wasn't making it up, she swore. And she put her stepsister, with whom she's been living since she got out of the state hospital, on the phone. "I can see them. They're moving down from her head to her eye," said Karen DeWeese. "They're about one and a half inches long and a half-inch wide. They look like bubbles under the skin." The ER doctor later found nothing.

The fibers, according to Harvey's theory, are really the hard shells, which he calls cuticles, that these worms shed at five stages as they grow from egg to larvae to adult. The red fibers are the males, he says. Blue fibers are female. "Using a 2,000-power microscope, you can see inside them," he says. "They look like little stovepipes to me. I can tell the blue ones are female because there's a kink in the middle for the sexual organs and some kind of pouch. And we have pictures of them laying thousands of eggs."

"If you write this theory, it's probably going to sound like someone's come from the mental institution," Harvey says. "But the fact is that this is a real disease, and it appears to be growing."

Some fellow Morgellons researchers -- many of whom were scheduled to meet at the University of Texas in San Antonio this month -- say Harvey's theory goes too far and that the fibers they've examined are in no way associated with any living organism.

"I have a lot of respect for him," Kilani said, "but his theory is really too far-fetched."

Sue Laws used to love to be outside gardening in the back yard of her Gaithersburg home. She also used to have a number of pet birds. Now, she can't stand to be in the yard. She says she feels as if she's being swarmed by insects. And the birds are long gone, a casualty of the family's move to a smaller house in Gaithersburg

She says she finally found some relief when she went to see James Matthews, a Gaithersburg family doctor. Matthews, who says he himself has Morgellons and offhandedly mentions aliens and conspiracy theories, puts his patients on a strict, experimental regimen of high-dose antibiotics, antiparasitic medication and antifungal cream that can run as much as $1,000 total. They're told to drink colloidal silver, which doctors used as an antibiotic before the 1930s and which the Environmental Protection Agency has approved for use as a disinfectant in hospitals; and they mix diatomaceous earth (made of the hard shells of sea creatures) into their food and take a variety of herbs such as ginkgo biloba, as well as vitamins and home remedies such as cod liver and coconut oils. Sue took the long lists Matthews gave her and didn't ask questions. High doses of colloidal silver can turn the skin permanently blue. Though the silver is legal to sell as a dietary supplement, the Food and Drug Administration maintains it has never been tested to prove any therapeutic value. But Sue was desperate to make the itching stop and says she was ready to try anything. "Forgive me, but I would have eaten dog doo at that point if they'd told me it would make me better."

The treatment is expensive, though Sue's insurance covers most of it. At her sickest, she still paid as much as $400 out of pocket every month for a host of antibiotics, fungicides, antiparasitics and other medications. She says she now pays about $100 a month out of pocket. Matthews, like Savely and Stricker, prefers not to work with insurance companies, and patients often pay out of pocket, sometimes $500 per visit. Matthews, who has since sold his family practice to study Morgellons full time, also receives a portion of the proceeds every time he sells a bottle of NutraSilver brand colloidal silver in his office. The money, he says, is used to further his Morgellons research.

The treatment hasn't cured her, Sue says. But the itching has subsided, and she's able to function. For the first time in years, her lesions have begun to heal, and she's been able to work and leave the house. She visited her daughters in Colorado in September and has gone with Leitao to the Capitol to lobby members of Congress for funding.

Matthews postulates that Morgellons is a coming epidemic. Everyone, he says, has fibers. To prove it, he asked for my hand. He cleaned a ProScope, which magnifies the skin 200 times, with alcohol, and I washed my hand with antibacterial soap. Under the microscope, there in my palm, was what appeared to be a tiny red fiber embedded in the skin. Under the top of my fingernail, I saw a bright blue one. Matthews smiled triumphantly. "You see," he said. "Everyone has Morgellons." Other doctors, told of the fibers, dismissed them, saying Matthews's microscope probably found red blood vessels close to the surface of my skin, or a blue-colored vein. But they weren't sure.

CDC officials have been sent images of fibers. But they decline to hazard a guess on what they could be. "We don't know anything about the patients from whom or the condition under which these were taken," spokesman David Daigle wrote in an e-mail. "They appear to be inanimate fibers. What they actually represent is not clear at this time, and we'd prefer not to speculate further."

These days, Sue is unconcerned about both the presence of the fibers -- she now uses a Shed Ender, a dog comb, to get them out of her hair -- and doctors' skepticism. What matters is that she has her diagnosis and a doctor who finally believes her. She has medications that give her a measure of relief. Still, she sits up half the night in her hard, wooden kitchen chair, afraid that lying down to rest in darkness will encourage whatever is in her to come alive and torment her again. She looks out into the black night and waits for a cure.

Brigid Schulte is a reporter for The Post's Metro section. She can be reached at schulteb@washpost.com.